The Andean Seasonal Calendar and Food Traditions (2025)

“In the Andes, time is not linear but cyclical. Every season brings its own wisdom, and each harvest teaches us to live in harmony with the Earth.” — Traditional Andean saying

Introduction

High in the majestic Andean mountains, indigenous communities have developed a profound relationship with their environment over thousands of years. This relationship is embodied in the Andean seasonal calendar—a sophisticated system that synchronizes agricultural activities, culinary traditions, and cultural celebrations with the natural rhythms of the Earth. Unlike the Western four-season model, the Andean calendar recognizes subtle shifts in climate patterns, astronomical events, and ecological indicators that guide planting, harvesting, and food preparation throughout the year.

Research from the International Potato Center in Peru reveals that traditional Andean farmers can identify over 30 distinct microclimates and environmental indicators that inform their agricultural decisions—a knowledge system refined over generations. This intimate understanding of seasonality doesn’t just ensure agricultural success; it shapes a culinary tradition that emphasizes eating in harmony with nature’s cycles for optimal nutrition and sustainability.

This guide explores the Andean seasonal calendar and its profound influence on food traditions, offering insights into how these ancient practices can enrich modern approaches to cooking and nutrition.

The Structure of the Andean Agricultural Calendar

The traditional Andean agricultural calendar divides the year into two major seasons: the dry season (tiempo de secas or ch’aki pacha in Quechua) and the rainy season (tiempo de lluvias or paray pacha). However, within these broader divisions exist numerous smaller periods marked by specific astronomical events, weather patterns, and ecological indicators.

Key Periods in the Andean Calendar:

- Preparation Time (April-August): The dry season when soil is prepared, terraces are maintained, and planning for the agricultural cycle begins.

- Planting Time (September-November): The beginning of the rainy season marks the time for sowing seeds, with specific dates determined by observing natural indicators and celestial events.

- Growing Time (December-February): The height of the rainy season when crops develop, requiring careful tending and protection.

- Early Harvest (March-April): When certain fast-growing crops and early varieties are harvested.

- Main Harvest (May-June): The principal harvest period for staple crops like potatoes, quinoa, and corn.

The Andean calendar is not simply marked by dates but by observing natural phenomena. Farmers watch for specific bird migrations, insect appearances, plant flowerings, and star positions to determine the optimal times for agricultural activities.

Learn more about traditional ecological indicators in our guide to Andean Bioindicators →

Astronomical Foundations of the Andean Calendar

The agricultural calendar in the Andes is deeply connected to astronomical observations. Traditional Andean cultures developed sophisticated understanding of celestial movements that informed their agricultural practices.

Solar Observations

Two major solar events anchor the Andean calendar:

- Inti Raymi (June Solstice): Marking the beginning of the agricultural year, this celebration honors Inti, the sun god, at the winter solstice in the Southern Hemisphere. Traditional communities gather at sacred sites like Sacsayhuamán near Cusco to observe the sun’s position and perform rituals for a bountiful year.

- Capac Raymi (December Solstice): The summer solstice in the Southern Hemisphere coincides with the early growing season and is celebrated with ceremonies to ensure healthy crop development.

Stellar Indicators

The appearance of specific star clusters guides agricultural timing:

- The Pleiades (Quechua: Collca): The visibility and brightness of this star cluster in early June is traditionally used to predict rainfall patterns for the coming season. Clear, bright Pleiades indicate a good agricultural year, while dim appearances forecast drought conditions.

- Southern Cross: Its vertical alignment indicates optimal planting times for specific crops.

Discover Andean star lore and its influence on seasonal cooking practices →

Seasonal Variability and Microclimates

The Andean region encompasses remarkable ecological diversity, with dramatic elevation changes creating distinct microclimates even within short distances. Traditional Andean farmers recognize and adapt to at least five major ecological zones:

- Yungas (below 2,300 meters): Tropical and subtropical valleys where fruit, coca, and other heat-loving crops flourish.

- Quechua Zone (2,300-3,500 meters): Temperate valleys ideal for corn, squash, and beans.

- Suni Zone (3,500-4,000 meters): Higher elevation areas perfect for potato, quinoa, and other frost-resistant crops.

- Puna Zone (4,000-4,800 meters): High plateaus used primarily for grazing but where bitter potatoes and other highly resistant tubers can grow.

- Janca Zone (above 4,800 meters): Snow-capped peaks, largely uninhabitable but spiritually significant.

Each zone follows its own seasonal rhythms, and traditional Andean communities have developed sophisticated systems of vertical control—cultivating crops across multiple ecological zones to ensure food security despite variable climate conditions.

Local microclimates create further diversity, with south-facing slopes (more shaded in the Southern Hemisphere) often planted with different crops than north-facing ones. Traditional farmers may plant up to 15 different varieties of a single crop like potatoes across their lands, each suited to specific microclimate conditions.

Explore microclimate cooking techniques in our guide to Andean Altitude Cuisine →

Seasonal Planting and Harvest Cycles

The Andean agricultural calendar centers around key staple crops, each with its own planting and harvest schedule carefully synchronized with seasonal changes.

Potato Cycles

As the cornerstone of Andean cuisine, potato cultivation follows specific seasonal patterns:

- Early planting (maway tarpuy): September-October for early-maturing varieties

- Main planting (hatun tarpuy): October-November for main crop varieties

- Late planting (mishka): December for late varieties

- Harvest: Beginning in March for early varieties, with main harvests in May-June

Different potato varieties—from the floury, high-starch huayro to the waxy, colorful papa nativa—are planted and harvested at staggered times to ensure year-round availability.

Quinoa and Andean Grains

The sacred grain of the Andes follows its own cyclical pattern:

- Planting: October-November, timed with the first reliable rains

- Growing: December-March, during the heart of the rainy season

- Harvest: April-May, when the quinoa panicles dry and seeds harden

Other Andean grains like kañiwa, kiwicha (amaranth), and tarwi (Andean lupin) follow similar but slightly staggered schedules, allowing farmers to distribute labor throughout the year.

Corn (Maize)

As a heat-loving crop, corn has its own distinct seasonal requirements:

- Planting: September-October in lower elevations; November in middle elevations

- Growing: Benefits from the warm, wet summer months (December-February)

- Harvest: Fresh corn (choclo) harvested February-March; dry corn in May-June

The diversity of crops and planting times creates a continuous cycle of planting and harvesting throughout the year, ensuring food security and diverse nutrition.

Learn about traditional storage methods to preserve seasonal harvests →

Traditional Food Preservation Methods

The seasonal nature of harvest in the Andes necessitated sophisticated preservation techniques to ensure year-round food availability. These methods, developed over centuries, not only extend food longevity but often enhance nutritional profiles and create entirely new food categories.

Dehydration Techniques

The dry, cold air of the high Andes creates perfect natural conditions for dehydration:

- Chuño: A freeze-dried potato product made by exposing potatoes to freezing night temperatures followed by intense daytime sun, then physically removing moisture by walking on them. The result is a long-lasting food that can be stored for years.

- Charqui: Similar to jerky, this technique preserves meat (traditionally llama or alpaca) by cutting it into thin strips, salting, and sun-drying for several days.

- Dried Fruits and Vegetables: From sun-dried capulí (Andean cherry) to dehydrated oca (an Andean tuber), numerous plants are preserved through controlled drying.

Fermentation

Fermentation serves both preservation and nutritional purposes:

- Tocosh: Potatoes fermented in water and then sun-dried, developing penicillin compounds and used medicinally.

- Chicha: Fermented corn beverage with both ceremonial and nutritional significance, prepared seasonally but with techniques to extend availability.

- Tarwi Fermentation: The bitter Andean lupin undergoes controlled fermentation to remove alkaloids and increase digestibility.

These preservation methods aren’t merely survival techniques but sophisticated culinary and nutritional practices that transform seasonal abundance into year-round sustenance while creating complex flavors and enhancing specific nutrients.

Discover traditional Andean fermentation techniques you can practice at home →

Seasonal Celebrations and Food Rituals

Throughout the Andean agricultural year, communities mark important seasonal transitions with ceremonies and rituals, almost always centered around food. These celebrations strengthen community bonds, express gratitude to Pachamama (Mother Earth), and ensure the continuity of agricultural knowledge.

Major Seasonal Celebrations

- Pachamama Raymi (August): Before the planting season begins, communities make offerings to Mother Earth, including a feast called apthapi where families bring different seasonal foods to share collectively.

- Potato Harvest Festivals (May-June): Villages celebrate the main potato harvest with rituals of thanksgiving, selecting the most perfect tubers for seed potatoes for the next year’s planting.

- Carnival (February-March): Coinciding with the first harvests of green crops, this celebration features dishes made with fresh corn, beans, and early tubers.

Ritual Foods and Their Seasonal Significance

Specific foods hold ceremonial importance at different times in the seasonal calendar:

- Quinoa Soup: Served during planting ceremonies as a symbol of hope for abundance.

- Twelve Fruits Ritual: During New Year celebrations, consuming twelve different seasonal fruits to ensure prosperity through all months of the coming year.

- First Harvest Offerings: The first fruits of harvest are always offered to Pachamama before general consumption begins.

These ceremonies maintain the relationship between communities, their food sources, and the natural cycles that govern agricultural success.

Experience traditional seasonal celebration recipes for your own home rituals →

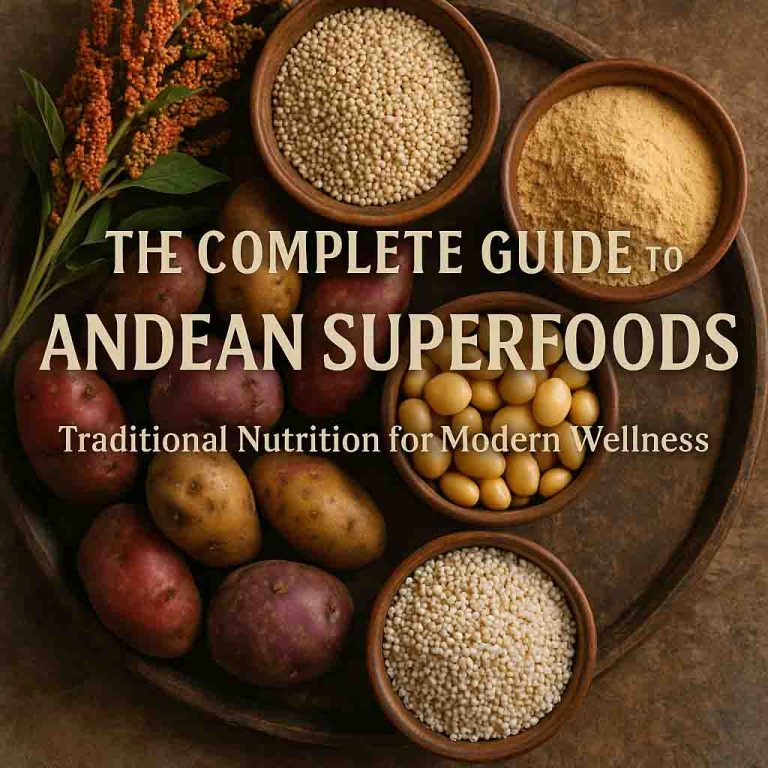

The Nutritional Wisdom of Seasonal Eating

The Andean seasonal eating pattern represents an intuitive nutritional wisdom that modern science now validates. By synchronizing diet with natural growth cycles, traditional communities access nutrients at their peak availability and adapt their nutritional intake to the body’s changing seasonal needs.

Seasonal Nutritional Patterns

- Rainy Season (Growing Period): Diets include more fresh greens, early tubers, and stored proteins. Fresh herbs and wild plants provide micronutrients during a time when stored foods may be depleting.

- Harvest Season: Abundance of fresh foods with peak nutritional content, eaten at their height of ripeness.

- Dry Season: Greater reliance on preserved foods rich in concentrated nutrients and complex carbohydrates to sustain energy during agricultural work.

Health Benefits of Cyclical Nutrition

Research from the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina in Peru has documented how traditional seasonal eating patterns naturally provide balanced nutrition throughout the year:

- Nutritional Diversity: By necessity, seasonal eaters consume a wider variety of foods than those with year-round access to all foods, increasing micronutrient intake.

- Adaptive Metabolism: The body develops resilience through adapting to seasonal nutritional changes.

- Peak Phytonutrients: Foods consumed in season contain higher levels of beneficial plant compounds, as shown in studies comparing in-season versus out-of-season produce.

This nutritional wisdom embedded in Andean food traditions offers valuable insights for contemporary approaches to healthy eating.

Learn how to apply Andean seasonal eating principles to your modern kitchen →

Modern Applications of Andean Seasonal Wisdom

The traditional Andean approach to seasonal eating offers valuable principles that can enhance modern culinary practices and nutrition, regardless of geographic location.

Adapting Andean Seasonal Practices

- Local Seasonal Awareness: While your local seasons may differ from the Andes, the principle of eating what grows naturally in your region during specific times remains powerful. Develop awareness of your local growing seasons and structure your diet accordingly.

- Preservation Techniques: Traditional Andean preservation methods like dehydration, fermentation, and root cellaring can be adapted to extend the seasonal bounty of any region.

- Mindful Consumption: The Andean tradition of honoring food sources and celebrating seasonal transitions encourages a more conscious relationship with food.

Practical Integration Strategies

- Seasonal Menu Planning: Structure your cooking around what’s currently in season locally, using Andean combination principles to create balanced meals.

- Preservation Projects: Dedicate time during harvest seasons to preserve foods at their peak, using adapted versions of Andean techniques.

- Community Connections: Participate in local food systems through farmers’ markets, CSAs, or food cooperatives to access truly seasonal products.

The Andean perspective offers not just techniques but a holistic philosophy that views seasonal eating as a way to maintain balance between human health, community wellbeing, and environmental sustainability.

Conclusion: Living in Harmony with Natural Cycles

The Andean seasonal calendar and its associated food traditions represent more than just agricultural practices—they embody a profound philosophy of living in reciprocity with the natural world. In an era facing climate unpredictability and disconnection from food sources, these ancient traditions offer timely wisdom.

By understanding how Andean communities have structured their relationship with food through careful observation of natural cycles, we gain valuable insights for creating more sustainable, nutritious, and meaningful food systems in diverse contexts around the world.

Whether you’re looking to enhance your nutrition, reduce your environmental footprint, or simply connect more deeply with your food, the principles of the Andean seasonal calendar provide a valuable framework. By observing local seasons, preserving abundance, and celebrating the cyclical nature of growth and harvest, we can bring the wisdom of the Andes into our own kitchens and communities.

Begin your seasonal journey today by exploring our supporting resources on Andean cooking techniques, preservation methods, and seasonal recipes that bring these ancient principles to life in the modern kitchen.

Related Resources

- Andean Bioindicators: Nature’s Signs for Seasonal Cooking

- Seasonal Preservation Techniques from the Andes

- Adapting Andean Seasonal Eating to Your Local Environment

- The Andean Superfoods Guide

- Traditional Andean Cooking Methods

- Seasonal Recipe Collection by Altitude and Climate

- The Ceremonial Foods of the Andean Calendar